What made you take Sandra Maischberger’s offer to make this film about Leni Riefenstahl?

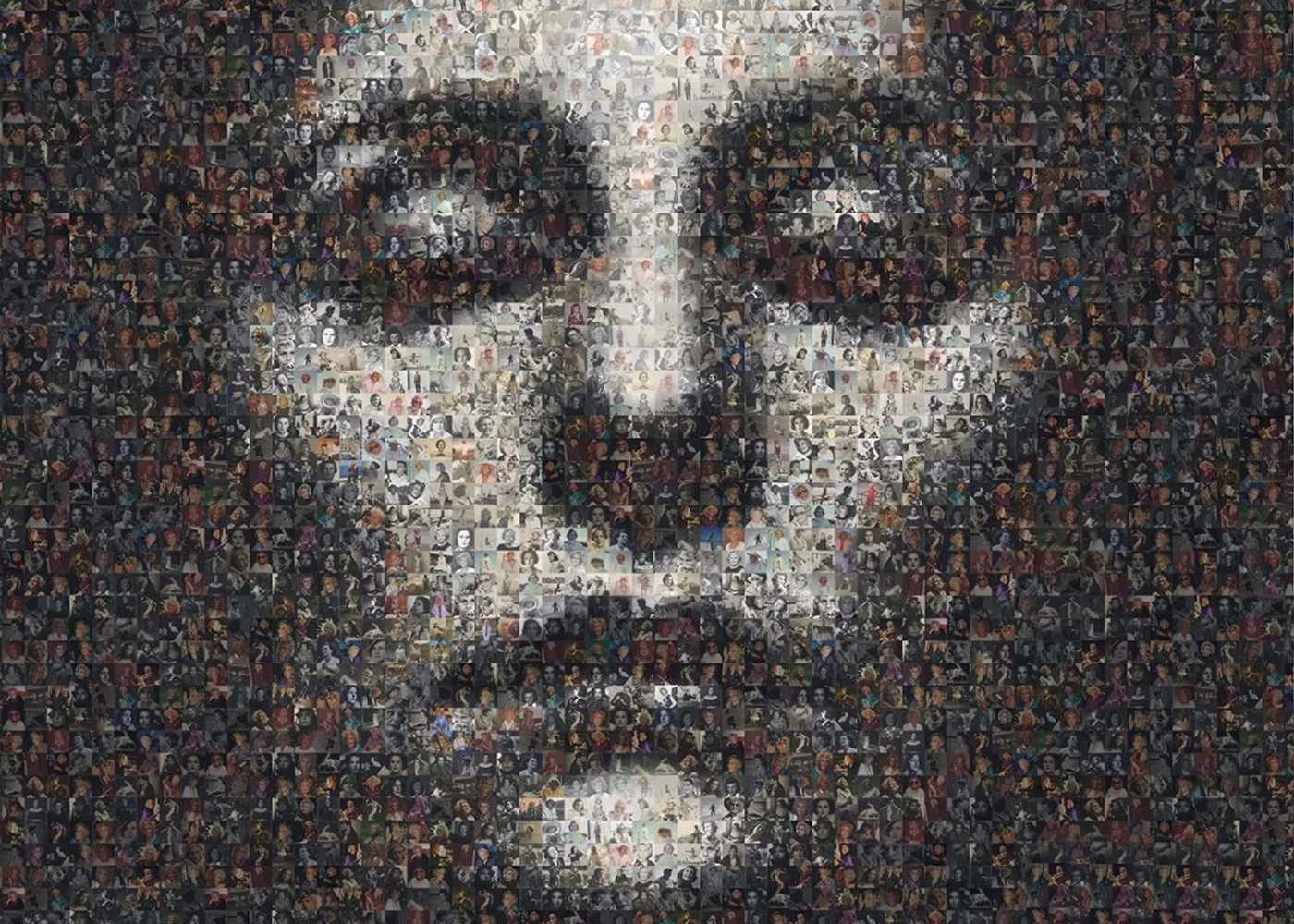

I was intrigued and ultimately seduced by what we found among the Riefenstahl Estate: you need to imagine 700 boxes spread over three museums, among them the Deutsche Kinemathek and the Photography Museum. I discovered private films, which I had never seen before, a lot of photos, but also written material like a diary—the drafts of her memoirs, which were quite different from the final printed version.

So my motivation was to get a deeper insight into who Leni Riefenstahl was, both as an individual and as a prototype of a fascist-to-be. But also, I was interested in asking what a biography like Leni Riefenstahl’s tells us about today.

Digging into the archives, did you discover anything you didn’t know before?

I realised Leni Riefenstahl was a National Socialist in her heart and remained one after the war and throughout her whole life. When you listen to the phone calls—she taped hundreds of hours of her own private phone conversations, many with the audience after talk shows—you realise how much she was stuck in the ideology.

When you think of her films, at first sight, they’re celebrating the strength and the supremacy of the German ‘race’. But on a deeper level, it comes down to a contempt for the “weak”, the sick. Just think how she reacted when her cameraman Willy Zielke was diagnosed with schizophrenia, admitted to a psychiatric ward, and ultimately forcibly sterilised. She didn’t intervene. Why? Because she was convinced that people like him were a threat to the German people. So she was a convinced National Socialist. She was really an enthusiastic reader of Mein Kampf—we have proof of it.

Her line of defence always was: “If I’m to blame for being a Nazi back then, then 95% of Germans should be as well.” As a viewer, the most difficult thing to assess is “how much did she really know?” Was she just another German Mitläufer, who happened to be extra-talented and got the means to make her films from the Führer himself?

First of all, she became a diehard sympathiser very early on. In a 1934 interview with the UK Daily Express, she described her experience of buying Mein Kampf when she was shooting The Blue Light and how she was immediately blown away—entranced by the book from the first page! So she was an enthusiastic National Socialist as early as 1931.

For sure, after the war, she denied responsibility by just saying, “I was never interested in politics. I was just an artist.” She repeated all the same excuses and legends with the same sentences in, I think, 500 interviews: “I had nothing to do with the regime,” which, of course, in her case, was a lie. In some cases, it’s not difficult to show she’s a liar. What’s interesting is to explore how her narrative evolved over time and why she lied—like with the Końskie episode.

Końskie is very interesting because, as you said, it shows how her narrative evolved over time. But also, from my perspective as a viewer, the truth is still unclear. What we know for sure: she went off to Poland with the Wehrmacht as a war correspondent, and on 12 September 1939, Polish Jews were shot while she was there. We have a photo showing her distressed and crying just after this, and we also know she asked to go back to Germany soon after. Then we have different stories.

We have three different stories. Until about 1952, she says, “I was the witness of the first massacre of Jews.” After 1952, she says, “No, I didn’t see any cruelties. I didn’t see the killing of the Jews. I just heard it. I was far away.” And then you have a third story that comes from a low-rank officer’s letter citing an army report—which we found among her archives. He says that while filming on the marketplace, she gave stage directions: “Jews out of the image,” which shows how antisemitic she was already—Jews looked dirty, and they were disturbing the pure image of German National Socialism. So if this is true, what the adjutant writes—though we have no other witnesses—she was the catalyst of a massacre.

The letter only says that her remark prompted them to try and flee and that shots were fired. But it doesn’t say she hated those Jews or meant to have them shot. What it does say is that at some point, she started to lie about what she knew. You get the feeling that on that day, she may have realised more than she was ready to acknowledge. To be honest, this is one rare moment when we feel that she’s capable of human empathy. A narcissist is forced to face the consequences of her actions…

If that’s the case, she immediately ran away from them and tried to deny them. First of all, it took, I think, more than four weeks till she really gave up her position with the Wehrmacht. She was still present at the Victory Parade in Warsaw. But anyway, the interesting point is why, after 1952, she started to lie. She could have used the photo and said what you just mentioned: “Listen, I was so shocked about what had happened. Look, I had tears. I was close to fainting with horror. And I did protest against what I saw,” which she did, in fact. But it was in contradiction with another statement. And that was her problem. Because until 1952, in the denazification trials, she always maintained: “I only learned about the horror of the regime after the war.” And so this was the contradiction. And that’s why she had to change it. So you can analyse how a truth turns into a lie. The fabrication of a “new truth.”

Your film also shows how, despite her best efforts and great skill in controlling her life narrative, she ultimately fails. We have known since Susan Sontag’s famous takedown what a master manipulator she was. But you bring fresh evidence—drawn from her own archives, which she had so carefully sorted and organised. And yet, truth trickles through…

Yes, I actually started with a great deal of mistrust because we knew she had manipulated her estate to suit her own life narrative. Naturally, I expected that she had destroyed all ‘compromising’ material. But then, and this was astonishing to me, she made a lot of mistakes. She left behind a wealth of incriminating evidence.

However, beyond exposing the lies, what really interested me was exploring why she lied. In that regard, I see her as a prototype of an entire generation. She was also a product of the education she received as a child from the previous generation. Remember when she recalled how her father threw her into the water and she almost drowned? She doesn’t blame him for nearly killing her. No. Instead, she says, ‘Well, thanks to this, I became a good swimmer.’ She is a prime example of the harsh, brutal education that shaped generations in Prussia—a country surrounded by France, Austria, and Russia—where people were trained to be “strong,” like the “Lange Kerls” of the Prussian army. Leni Riefenstahl’s upbringing reflects how an entire generation was primed to become good fascists.

Do you also see her post-war denial as mirroring the attitude of her entire generation towards their Nazi past? There’s an incredible talk show you feature in the film, where she is confronted by a woman who resisted the Nazi regime. Riefenstahl behaves as though she is the victim, ‘scapegoated’ for atrocities she claims she had no involvement in. You also show how a large part of the audience’s sympathy goes out to her.

Yes, for me, that talk show is emblematic of post-war Germany in the 1970s. Germany had taken some steps towards confronting its past, such as the Auschwitz trials in the 1960s and the protests of the ’68 movement against Chancellor Kiesinger, who had served in the Reich Propaganda Ministry. But the reality was that a vast majority of Germans were simply tired of the so-called Vergangenheitsbewältigung—‘no more dredging up the ugly past, we want to look towards the future!’ So you see how Riefenstahl received hundreds of fan letters and just as many phone calls offering support and sympathy. They truly loved Leni Riefenstahl!

You hear the same rhetoric from the AfD today: how Germany is so much more than those 12 years, and how ‘we are sick of being guilt-tripped about the past over and over again.’ Like Riefenstahl, they long for the lost ‘glorious’ days of virtue and order. She herself was convinced those days would return—that there would be a renaissance of National Socialist ideals. Today, that feels like a dark prophecy.

In her famous essay on Riefenstahl’s 1973 book about the Nuba, Susan Sontag denounced her renewed popularity as a symptom of a sick fascination—a longing for fascist aesthetics. So this phenomenon extends far beyond the German political context…

Yes, absolutely. Her work on the Nuba was celebrated internationally—it was huge in Japan, where she had a few big solo exhibitions. She was also widely admired in the US, both for her Nuba photo book and for her films. In 1974, she was a guest of honour at the Telluride Film Festival alongside Coppola, which provoked Sontag’s outrage: ‘Do you really know who you are celebrating?’

Leni Riefenstahl was a master manipulator of images, shaping them to tell her own ‘truth.’ With this documentary, you are now the director, in control of the selection of images and, ultimately, of the narrative. It’s a dialectical reversal of power—and a huge responsibility. How did you navigate that?

For me, it was crucial not to stage a tribunal, to retain some ambiguity. For example, in the scenes with the Nuba, it would have been easy to select only the moments where she appears to be exploiting people. But I also included scenes of tenderness with the children. I was actually criticised for the childhood scenes—some saw it as an attempt to exonerate her by portraying her as a victim. But it was really important to see her as a human being too. And this was a challenge, to accept that she was not some monster, but a German woman of her days, and an ambitious artist who scored the job of making Olympia as a director, getting all the possibilities—and she used them. But then, you have to be very precise, you have to show the responsibility. There’s no way out. She was a believer and a propagandist. That’s why the analysis of her as a prototype of fascism is so important to me. And this is the real tightrope walk: understanding her as a human being, but leaving no space for exoneration, no letting her off the hook. Because she’s part of us, and that’s the real danger. She’s not some alien, some evil alien.

Does this mean that as a filmmaker, you asked yourself what you would have done in her place—if you had been given the same privileges and unlimited resources that Riefenstahl received to make the films you dreamed of?

Yes, of course. And I don’t know how I would have responded. That is exactly the point. If someone offers you everything you ever wanted—unlimited resources to create something you have always dreamed of—it is seductive. But acknowledging that does not exonerate her. And it does not exonerate us.

We live in an era where many of the ideals Riefenstahl glorified in her films, and longerd for in her heart, are making a comeback: the desire for authority, the longing for order, decency, and virtue; the feeling of belonging to a nation that is greater than others and needs to be protected from unwanted and corrupting “others”. These sentiments are in the air once again. And I think Riefenstahl’s story offers a chance for introspection.